By James MOLESWORTH

At Rotem & Mounir Saouma, a Little Bit of Everything

But there’s nothing ordinary about this young Rhône domaine

There are different ways to create a domaine. Most who start from scratch build up slowly, progressing linearly, either growing in size and/or refining or evolving their style over the years.

Or you can go about it in a completely different way, experimenting, exploring tangents and basically doing things that people tell you not to do.

« I have people stopping when they see my vineyard and coming to tell me I’m crazy. They say ‘You can’t do it that way.’ And I say, ‘Why not?’ » said Mounir Saouma.

Lebanon-born Saouma, 47, has earned a name for himself with his Lucien Le Moine line of Burgundies, a micro-négociant operation where the cellar typically has 75 different wines in just one- or two-barrel lots. Saouma is taking the same micro approach to his Rhône operation, which he started in 2009 with a purchase of a handful of acres in the Pignan lieu-dit. After another purchase just recently, Saouma now has 15 acres in Châteauneuf and 22 acres of Côtes du Rhône-Villages around his Rotem & Mounir Saouma winery in Massif d’Uchaux.

« I love Burgundy of course, but I’ve been drinking Châteauneuf all along as well, » said Saouma. « I love the similarities of Pinot and Grenache. Both make silky, elegant, minerally wines and there is the parallel of each having Noir, Blanc and Gris versions as well. »

Saouma takes his immigrant, do-it-yourself mentality into the vineyard with him. He’s bought parcels that have been mismanaged but are situated in good terroir. He slowly rejuvenates them, replacing dead vines, increasing density and getting the plots back into balance.

« It’s like adopting a baby, » he said. « Bloodlines are important, sure. But really what you do and how you raise the child, from three weeks old to a teenager, is more important. »

Saouma vinified his 2009s in the Famille Perrin facility, and he counts the Perrins, as well as Henri Bonneau, Laurent Charvin and Ogier’s Jean-Pierre Durand among his friends in Châteauneuf. He laughed as he talked about how they’ve just as often scratched their heads as encouraged him, though, as he has taken dramatically different approaches to winemaking.

Saouma practices extremely long élevages, sometimes up to 60 months, during which time the wines stay on their lees unracked and unsulphured. As he prefers particularly cold cellars, his alcoholic and malolactic fermentations can stretch on for well over a year, with the resulting blanket of CO2 these long, slow ferments produce acting as protection in lieu of sulphur (though he does add sulphur before bottling). While the wines are left untouched for long periods, I find the approach still very interventionist—choosing not to do things is just as much a part of the process as choosing to do something. Nonetheless, Saouma feels he is a minor part of the process.

« I’m not doing the malo on the ’13 now, » he said, stressing « I’m. » « The malo is just happening. It’s not me and I don’t have an explanation for it. But I do know that the wine has to learn to deal with oxygen. If you sulphur early, it’s like sheltering a shy child. They will never blossom. »

Reds here are fermented with partially whole clusters—Saouma sets his destemmer to destem large berries, partially destem midsize berries, and leave the stems on the smaller berries. From there, the grapes receive a long cold soak, sometimes over a week.

« This extracts firm but fine tannins, as the extraction is not being done by heat or alcohol, » said Saouma. After the cold soak, the temperature control in the cement vats is turned off and the ferments start naturally from there, albeit slowly. There is no remontage or pigéage. The wines are then pressed off in a small vertical basket press, with both free-run and press wine used, but at very light pressure.

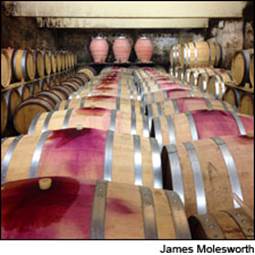

There’s a little bit of everything in this cellar, including clay amphora that Saouma is trying out. There’s also five vintages of free-run only juice, from Pignan, all in barrel and all still untouched—the 2009 will finally be bottled in September after its 60-month élevage and is set to be called Le Petit Livre. But what looks a bit like a scattershot, mad-professor approach, is actually lucid, well-planned, serious winemaking. It’s not tinkering for tinkering’s sake, but a desire to find out what wine can really do. Saouma’s wines are not for the uninitiated, but they are beautiful, flowing, sublime, mineral- and fruit-laden expressions of both place and vigneron.